Protein

TODO:

Conformation

When selecting a protein structure for molecular docking, the choice between an apo (unbound) or holo (bound) structure is an important consideration. The conformation of the protein can significantly influence the docking results and the predicted binding modes of the ligands.

Ligand-bound structures usually outperform ligand-free structures, as the geometries of the binding pocket are better defined in the bound state than in the unbound state. When a ligand is bound to the protein, it induces conformational changes in the binding site, optimizing the pocket for favorable interactions. These induced-fit effects are captured in the holo structure, providing a more realistic template for docking simulations. In contrast, apo structures may have a less defined or altered binding pocket geometry, as the absence of a ligand can allow for more flexibility or different conformational states.

If a holo structure is not available, computational tools such as SphGen, SiteMap, fpocket, and FTMap can be used to identify potential ligand binding sites. These tools employ various algorithms to predict and characterize binding pockets based on the protein's surface properties, such as shape, electrostatic potential, and hydrophobicity.

However, there are situations where apo structures can still be valuable. For example, if the goal is to identify novel binding sites or explore the protein's conformational flexibility, using an apo structure may be advantageous. Additionally, if the available holo structures have ligands that are significantly different from the ligands of interest, using an apo structure might be more appropriate to avoid bias towards a specific ligand class.

It is also important to consider the quality and resolution of the protein structure. High-resolution structures (e.g., those determined by X-ray crystallography) are preferred for docking studies, as they provide more accurate atomic coordinates. However, if high-resolution structures are not available, homology models or structures derived from other experimental techniques (e.g., cryo-electron microscopy) can be used, albeit with caution.

Mutations

It is crucial to use the wild-type protein structure rather than mutant structures.

However, if a wild-type protein is not available the next best option is to use the minimally mutated structure. Mutant proteins are often used in structural studies due to their enhanced stability, improved crystallization properties, or other biochemical reasons. However, these mutations can alter the protein's structure and function, particularly if they are located within or near the ligand binding site.

To ensure the accuracy and biological relevance of the docking results, it is essential to revert any mutations present in the protein structure back to the wild-type sequence. This process involves carefully examining the protein structure and identifying the mutated residues. Once identified, the mutated residues should be computationally replaced with the corresponding wild-type residues.

It is important to consider the potential structural consequences of reverting the mutations. Mutations can cause local conformational changes in the protein structure, which may affect the shape and properties of the ligand binding site. Therefore, after reverting the mutations, it is advisable to perform energy minimization or structural refinement to allow the protein to adjust to the wild-type sequence and adopt a more natural conformation.

In some cases, the structural impact of reverting mutations may be minimal, especially if the mutations are located far from the ligand binding site. However, if the mutations are within or in close proximity to the binding site, their reversion can significantly influence the docking results. Neglecting to revert such mutations may lead to inaccurate or misleading predictions of ligand binding modes and affinities.

Missing atoms

It is essential to address any missing atoms, side chains, or loops in the experimental protein structures before performing protein-ligand docking. Incomplete protein structures can arise due to limitations in crystallographic resolution, disorder, or experimental challenges.

When preparing the protein structure for docking, special attention should be given to missing side chains and loops that are in close proximity to the binding site. These missing elements can have a significant impact on the shape, size, and chemical properties of the binding pocket, ultimately affecting the accuracy of the docking results.

To address missing side chains, computational tools can be employed to model and reconstruct them based on the available backbone information and known amino acid sequences. This process involves predicting the most likely conformations of the missing side chains while considering their interactions with the surrounding residues and the overall protein structure.

Similarly, missing loops near the binding site should be carefully modeled and reconstructed. Loops often play crucial roles in protein function and can influence ligand binding by providing flexibility or forming important interactions. Modeling missing loops can be challenging, as they often exhibit higher flexibility and variability compared to other parts of the protein. Advanced loop modeling algorithms, such as those based on homology modeling or de novo structure prediction, can be utilized to generate plausible loop conformations.

However, it is important to exercise caution when dealing with regions of the protein structure that are weakly defined by experimental observables. These regions may have low occupancy, high displacement parameters (B values), or poor electron density in the crystallographic data. In such cases, the modeled side chains or loops should be examined critically, as their conformations may be less reliable. It may be necessary to consider alternative conformations or to treat these regions with a higher degree of flexibility during the docking process.

Water molecules

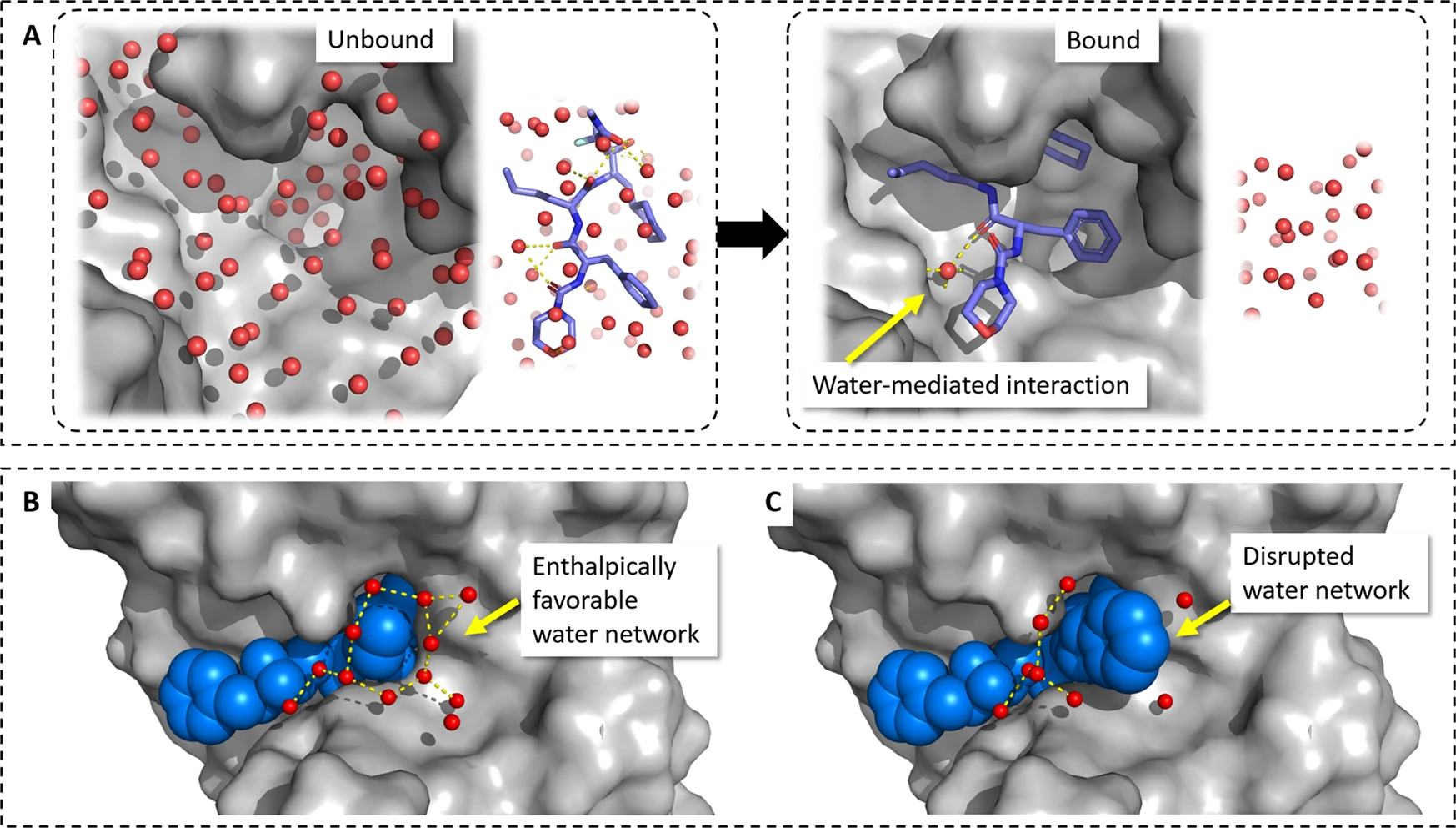

When preparing protein structures for docking studies, the treatment of water molecules is a critical consideration that can significantly impact the accuracy of the results. Water molecules can play various roles in protein-ligand binding, and a careful analysis is necessary to determine which water molecules should be included or excluded in the docking process.

In some cases, water molecules can mediate important interactions between the protein and ligand by forming bridging hydrogen bonds that stabilize the binding. Excluding such bridging water molecules from the docking procedure could lead to incorrect predictions of ligand poses and binding modes. For example, in docking studies of EGFR kinase inhibitors, researchers found that including a key bridging water molecule was essential for correctly reproducing the experimentally observed binding modes. When this water was excluded, the docking results yielded incorrect ligand poses.

On the other hand, some water molecules may need to be displaced upon ligand binding. If a water molecule is energetically unfavorable or prevents optimal ligand contacts, it will likely be replaced by the ligand during the binding process. Including such water molecules in the docking procedure could hinder the identification of the correct ligand pose.

To make informed decisions about which water molecules to include or exclude, a careful examination of the available data is necessary. Crystallographic evidence of strongly bound water molecules, particularly those that form multiple hydrogen bonds with the protein and/or ligand, suggests that they should be retained in the docking process. Conversely, water molecules with high B-factors or incomplete electron density are less likely to be critical for ligand binding and can often be safely removed.

Computational methods can provide valuable insights into the thermodynamic properties of binding site water molecules. For example, the WATsite approach, which utilizes molecular dynamics simulations, can help identify the energetic favorability of individual water molecules in the binding site. This information can guide decisions on which water molecules should be included as part of the protein structure for docking.

Buffers

It is important to consider the presence of buffer components such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) and salts. These components are often used in protein crystallization to promote the formation of well-ordered crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction experiments. However, these molecules are typically not physiologically relevant to the protein's function and are specific to the crystallization conditions.

In most cases, buffer components like PEG and salts should be removed from the protein structure before conducting docking studies. These molecules may interfere with the docking process by occupying potential ligand binding sites or by altering the electrostatic properties of the protein surface. Removing these components allows for a clearer assessment of the ligand-protein interactions without the influence of artifacts introduced by the crystallization conditions.

There are some exceptions to this general rule. In rare cases, buffer components may mimic the interactions of a ligand or play a role in stabilizing a particular protein conformation relevant to ligand binding. In such instances, it may be appropriate to retain these molecules in the docking study. However, these cases are uncommon, and the decision to include buffer components should be based on a careful analysis of their potential impact on the ligand binding process.

Cofactors

The accuracy of docking results can be significantly influenced by the presence of cofactors, such as heme groups or metal ions, which are often essential for ligand recognition and binding. Cofactors are non-protein chemical compounds that associate with proteins and are necessary for their biological activity. In many cases, cofactors directly participate in ligand binding by forming interactions with the ligand or by inducing conformational changes in the protein that facilitate ligand binding. Therefore, the inclusion of cofactors in protein-ligand docking can be crucial for obtaining reliable and biologically relevant results.

When deciding whether to include cofactors in a docking study, several factors should be considered.

- The biological relevance of the cofactor must be assessed. If the cofactor is known to be involved in ligand recognition or is located in the binding site, it should be included in the docking process. Omitting biologically relevant cofactors may lead to incorrect binding poses and inaccurate affinity predictions.

- the availability of high-quality structural data for the protein-cofactor complex is essential. X-ray crystallography or NMR structures that include the cofactor provide the necessary information for accurate docking.

- the chosen docking software should support the inclusion of cofactors. Some docking programs have specific features for handling cofactors, such as the ability to define custom atom types or to specify the coordination geometry of metal ions. Finally, including cofactors in docking simulations can increase the computational complexity and resource requirements. The additional atoms and potential interactions introduced by the cofactor may lead to longer computation times and higher memory usage.

In cases where the cofactor is not directly involved in ligand binding or is located far from the binding site, its inclusion may not be necessary. However, if there is evidence that the cofactor induces long-range conformational changes in the protein that affect ligand binding, it should be considered in the docking process. In conclusion, the decision to include cofactors in protein-ligand docking should be based on a careful evaluation of their biological relevance, the availability of structural data, the capabilities of the docking software, and the computational resources at hand. When cofactors play a significant role in ligand recognition, their inclusion is essential for obtaining accurate and reliable docking results.

Protonation states

-

Bender, B. J., Gahbauer, S., Luttens, A., Lyu, J., Webb, C. M., Stein, R. M., ... & Shoichet, B. K. (2021). A practical guide to large-scale docking. Nature protocols, 16(10), 4799-4832. DOI: 10.1038/s41596-021-00597-z ↩